In Honor of Black History Month-A Salute to Black Cyclists in US History

We are sharing two inspiring stories about Black cyclists who paved the way for freedom and equality. Keep reading to learn about the 19th-century female transportation pioneer Katherine T. “Kittie” Knox and “The World’s Fastest Man” Marshall “Major” Taylor. We honor these heroes and work together toward a brighter future following in their steps.

Katherine T. “Kittie” Knox bravely confronted the racial and gender barriers

of the late 19th century

Photo Credit: League of American Bicyclists

Born in Boston, Katherine T. “Kittie” Knox (1874-1900) worked as a seamstress but discovered a passion for bicycling. She was a talented bike rider and a member of Boston’s Riverside Cycling Club, one of the country’s first Black cycling groups. She challenged the idea that bicycling was an activity meant for men and often finished ahead of her male competition in bicycle races. Knox insisted on riding her bicycle in baggy trousers instead of the long skirts that women were expected to wear at the time. She joined the overwhelmingly male-dominated League of American Wheelmen (LAW), the predecessor to today’s League of American Bicyclists (LAB).

In 1894, LAW banned Black people from belonging to the organization. Knox challenged this head-on. She showed up at LAW’s annual meeting in 1895 to present a certificate confirming that she had joined prior to the group’s “white only” membership policy. Several LAW members came to Knox’s defense, but many others expressed strong objections to her attendance and she was kicked out of the meeting. This sparked debate between LAW members who wanted to uphold racial segregation and those who felt that racial segregation was wrong. Kittie Knox was eventually accepted by LAW, making her the first Black person to be recognized as a member of the organization.

Kittie Knox helped to desegregate the bicycling world. She is celebrated around the United States as a champion of racial and gender equality in bicycling. Her grave at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, MA is now part of the African American Heritage Trail. In 2013, the City of Cambridge issued a Kittie Knox proclamation to celebrate her life and later named the Kittie Knox Bike Path after her. The League of American Bicyclists recently presented its first annual Katherine T. “Kittie” Knox Award, which recognizes a champion of equity, diversity, and inclusion. Ayesha McGowan, the nation’s first Black woman pro-racer, won the Kittie Knox award for her competitive example, her accomplishments, and her voice pushing for more inclusion in bicycling.

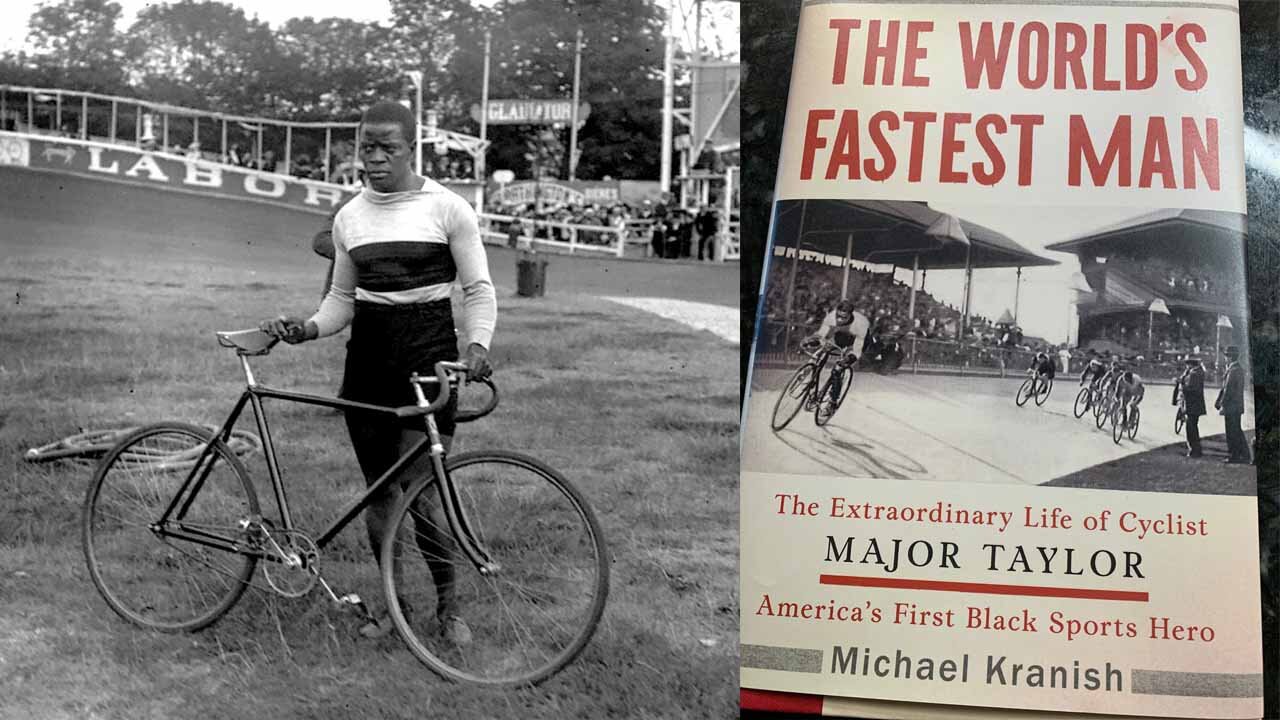

Major Taylor: The First Black World Champion Cyclist

More than 100 years ago, one of the most popular spectator sports in the world was bicycle racing and one of the most famous racers was an American man named Marshall Walter “Major” Taylor. Major Taylor (1878-1932) was the first Black world champion in cycling and the second Black athlete to win a world championship in any sport. He overcame racial barriers in an overwhelmingly white field bent on stopping him.

Major Taylor was given a bicycle at the age of 12. His first job was in a bike shop in Indianapolis, Indiana, where he performed bike tricks to entertain customers while dressed in a military uniform. This uniform is the source of the nickname “Major,” which stuck with him throughout his career.

Taylor began to race bicycles but he encountered discrimination at every turn. White cyclists would intentionally crash into him to prevent his victory. Spectators were just as nasty, throwing water in his face or putting nails on the road in front of his bike when he raced. Racetrack owners would refuse to let him compete. Professional cycling leagues such as the League of American Wheelmen adopted racist membership policies, preventing him from joining the organization while continuing to profit from his participation in their races.

Convinced Taylor would be a star, bike manufacturer and former racer Louis “Birdie” Munger gave Taylor a job as a bike mechanic and sponsored him in races. In 1896, Taylor officially turned pro and moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, the capital of US cycling at the time. From 1896 to 1910, Major Taylor was the LeBron James, Michael Jordan, and Jackie Robinson of his time. He set seven bicycle sprinting world record times and earned the title of “world champion sprinter” at the 1899 World Cycling Championship in Montreal, Canada.

Taylor endured remarkable prejudice while living under the Jim Crow era of racial segregation and he retired from professional racing in 1910, citing the increasing physical and mental toll of the sport. In his retirement he wrote his autobiography, “The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World.” He faced open racism and hostility with remarkable poise, perseverance, and dignity.

“Life is too short for a man to hold bitterness in his heart.”

-Marshall WAlter "Major" Taylor

Taylor passed away in Chicago in 1932 and was buried in a humble grave. In 1948, a group of cyclists organized his reburial. Taylor’s remains were moved to a more prominent location in Mt. Glenwood cemetery, marked by a plaque memorializing his contributions to the sport of cycling and the desegregation of professional athletics in the US. The City of Chicago named the Major Taylor Trail in his honor, one of Chicago’s urban bike trails connecting to neighborhoods on the city’s southwest side. Other cycling clubs, trails, places and events have been named in Major Taylor’s honor, including the Major Taylor Velodrome in Indianapolis and Major Taylor Boulevard in Worcester, Massachusetts.